EXCERPTS Ross Mackay: A Brilliant Criminal Lawyer

Full Title: Ross Mackay: The Saga of a Brilliant Criminal Lawyer and his Big Losses and Bigger Wins in Court and in Life

Enjoy a reading of the Prologue from Ross Mackay. Narration by Lorene Shyba.

Excerpt from the Prologue of Ross MacKay

by Jack Batten

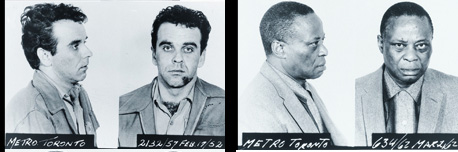

The voices in Ross Mackay’s dreams haunted him every night of that summer of 1962, two men’s voices murmuring in grief and dismay through Ross’s agitated sleep. Ross recognized the voices. That was no mystery. They belonged to Arthur Lucas and Ronald Turpin, two men who were now on Death Row in the Don Jail in Toronto waiting to be hanged by the neck until they were dead.

In two separate trials for two unrelated murders held nineteen days apart in the same Toronto courtroom that spring, the jury in the first trial convicted Lucas of capital murder, and the second jury convicted Turpin of the same offence. Each of the two judges sitting on the separate trials condemned the two men to the gallows. Everything was different about the murders—each was hideous in its own way—but one element linked the two trials. The common thread was Ross, the criminal lawyer who defended both accused men. Ross performed brilliantly in court—the judge in each case said exactly that—but his arguments, cross-examinations and jury addresses were not enough to fend off the guilty verdicts and the hanging sentences. Ross was left distraught, alone with the whispers of the two doomed men through the summer nights of his tormented dreams.

Excerpt from Chapter 24 of Ross MacKay

by Jack Batten

It wasn’t just his relationship with Rita that Ross’s drinking sabotaged. It began to affect his appearances in court. Battling the mother of all hangovers every morning, Ross made an unfortunate habit of tardiness to court. In Magistrate’s Court, where Ross spent more than half his working hours in criminal hearings, cooperative Crown Attorneys developed the custom of dispatching junior counsel to the Victoria Hotel to rouse Ross and steer him to court. On his own, a disheveled Ross often showed up in the early morning at United Deforest, a dry cleaning store next to the Brown Derby; Ross stripped down and sat in a back room with cups of coffee, while the employees drycleaned his suit, washed and dried his socks and underwear, even shined his shoes, and sent him to court looking and smelling fresh. Often Magistrates delayed the start of court by a half hour on days when Ross had a case before them. Crowns and Magistrates who appreciated the inventiveness of Ross’s advocacy were willing to cut him some slack, though God knew this could hardly be a permanent adjustment in courtroom scheduling.

It was in this period, so dangerous to Ross’s career, that Abbey Solomon took it on himself to act as Ross’s own personal wake-up service. Many mornings, on court days, Solomon arrived at Ross’s hotel room, poured him a shot of vodka to clear his head, then pumped in enough coffee to sober him up. It amazed Solomon how precisely Ross’s mind worked in court once he got there. He may have smelled like a bar room and his head may have been splitting with hangover pain, but Ross’s grasp of the law remained in place, his sense of tactics as reliable as ever. Sometimes Solomon included in these morning missions his partner in burglary. He was Joe Marcoux, the hard case whose approach to waking Ross tended to the extreme. More than once, he dumped a pail of cold water on the sleeping Ross. In Solomon’s description, “Ross would come flying out of the bed like he was Wile E. Coyote walking on air.”

Still, valiantly as Ross may have performed in his hungover state, he was flirting with danger, particularly in appearances before the Court of Appeal. Judges at this level hadn’t the patience that their colleagues in the Magistrate’s Court extended to Ross. Serious jurisprudence was at issue in the Appeal Court. Decorum needed to be observed. Counsel must present the most acute and discerning workings of their legal minds to engage in the arguments. At his best, Ross was the very model of a barrister before the court. At his hungover worst, he struggled not to self-destruct.