Excerpt from Florence Kinrade: Lizzie Borden of the North

By Frank Jones

Enjoy a reading of the Preface from Florence Kinrade. Narration by Lorene Shyba.

Preface: Do you think I did it?

The Florence Kinrade case has been on my mind for a long time. Since January 1987, in fact, when I picked up the phone to call her nephew, Ken Kinrade, who was wintering in Clearwater, Florida.

“Ken Kinrade?”

“Yeah, that’s me,” came back a harsh, raspy voice. I half-expected Kinrade, then in his seventies, to rebuff me. People, I’ve found, are generally not eager to discuss a murder in the family, even a long-ago one. But the voice was deceptive. Kinrade, I found when I met him on his return to Hamilton, Ontario in the spring, was a kindly, even timid man, happy to share what he knew about that shocking 1909 crime that had made the family’s name notorious.

Now it’s been thirty years since I made that phone call. Ken is long dead, as are several of the people who helped me reconstruct the lives of Florence, her sister, Ethel, and their well-to-do parents. The Rev. Graham Cotter, a nephew of Florence’s fiancé, Monty Wright, and a long-retired Anglican clergyman whose letter to me led me to the most important revelations of all, has been unfailingly patient as he waited for the story to be finally told. My manuscript languished on a shelf at the University of Toronto Press for several years. And then, like so many neglected projects, it continued languishing.

But the murder of Ethel Kinrade that snowy day in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada in 1909 deserves our attention because it uncovers a rich vein of social history. It tells us a lot about the obstacles an ambitious young singer from an upper-class family faced in seeking a career in – horrors! – vaudeville. It tells us about a forgotten underclass – the thousands of tramps who rode the rails of North America in that era and who were often the first to be suspected when a crime occurred. It tells too of the sometimes-odd practices of the psychiatric profession in that pre-Freudian time. And it also tells the story of a formidable woman who was as resilient as she was devious and was, quite simply Canada’s Lizzie Borden.

The parallels with the notorious 1892 Fall River, Massachusetts case in which Lizzie was suspected of the axe murder of her father and stepmother, are uncanny. In giving her testimony at the inquest into the death of her parents, Lizzie has been described as, “circling, evading, contradicting, revising her story as she went along, scorning the badgering of District Attorney Hosea Knowlton.”

The description could just as easily have applied to Florence who, from the first hours after she ran into the street crying that Ethel had been shot – six times – told different and contradictory versions of the murder of her sister. Ultimately, the newspaper-reading public followed with fascination her epic duel with one of the great counsel of the day, George T. Blackstock Q.C. at an inquest which was described by Coroner Dr. James Anderson, as, “unparalleled in the history of Canada, not only for the interest it has aroused throughout the whole country, but by reason of the legal points raised.” Dr. Charles Kirk (C.K.) Clarke ‘the father of Canadian psychiatry,’ who watched Florence throughout and interviewed her several times, said of her testimony, “a more startling and complex psychological study has rarely been offered.”

Edmund Lester Pearson, America’s pre-eminent crime essayist of his era, wrote that the Lizzie Borden case “is without parallel in the criminal history of America. It is the most interesting, and perhaps the most puzzling murder which has occurred in this country.” The same can be said of the Kinrade mystery – up north in Canada.

Pearson suggested that the Borden case had retained its fascination because it involved a class of people not normally involved in bloody crime, because it was purely a problem of murder, uncomplicated by sexual passion, and because it divided national opinion on the guilt or innocence of Lizzie Borden (who was subsequently but never convincingly judged innocent at her trial). The parallels hold. The Kinrade case too involved a well-off family; it was a ‘pure’ murder and one of shocking violence; it was, and remains, a mystery as to motivation, and it divided the public on the question of Florence Kinrade’s guilt or innocence.

So why hasn’t the Kinrade case caught the public’s imagination until now – say on a Lizzie Borden scale? Of course, there was a coroner’s inquest that went on for many weeks that was reported verbatim in the newspapers. Day after day, Florence was tested ruthlessly in the witness box by Blackstock, the Crown’s lawyer. In addition, reporters interviewed everyone with the remotest connection with the case in Canada and in Virginia, where Florence led a clandestine existence. Without a transcript of the inquest, I compared the multiple newspaper accounts of the coroner’s inquest. Particularly in the moments of high courtroom drama, I found Kit Coleman, Canada’s first female war correspondent, an invaluable mood and scene-setter whose reports I have made generous use of. By a stroke of luck, we also have the detailed psychiatric notes of Dr. C.K. Clarke.

The facts were laid shockingly bare. But Florence was never charged with murder. The inquest did not lead to a trial, meaning there was no official transcript to frame an account. And while she was still alive (she died in 1977), any careless accusation of guilt might have invited a civil suit.

All that the Kinrade mystery seems to have lacked in securing its place in history is the nursery rhyme factor: Lizzie Borden’s fame was enshrined with a rhyme chanted by generations of American children:

Lizzie Borden took an axe,

And gave her mother forty whacks.

When she saw what she had done,

She gave her father forty-one.

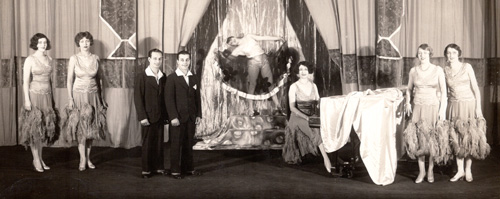

Nevertheless, Florence’s life following that period of high notoriety in 1909 was full of interest and surprises. Against all odds, she did achieve a career in vaudeville, endured years of misfortune and then, still singing the songs of her golden years, died at an advanced age and was buried in the Hollywood Cemetery alongside some of the film capital’s greats. A puzzle was Florence Kinrade; an enigma, larger-than-life woman who in her last encounter with her daughter asked provocatively, “Do you think I did it?”

— Frank Jones, 2019